Photo credit: Lauren Nicole Smith

What Does PoP Do To Support Public Education?

Pencils of Promise (PoP) implements programming in public schools to support public school teachers. We partner closely with Guatemalan communities dedicated to their education: firstly, we build public schools after forming a committee with local stakeholders and conducting a carefully contextualized Needs Assessment. Then, in as many as feasible PoP-built schools, we provide Teacher Support (TS) components to train public school teachers (and we provide materials like books and e-readers) to strengthen students’ reading, writing and comprehension.

Incredibly, Guatemala’s 2019 TS program supported 145 teachers across 19 schools. TS programming benefited over 4,000 students this year. Key components of PoP’s TS program include:

- Group teacher workshops. Each workshop consists of 4 hours of literacy pedagogy, 2 hours of WASH training, and 2 hours of socioemotional and class management support. These workshops are intended to build and solidify new pedagogical methods into classroom instruction for the curriculum provided by the Guatemalan Ministry of Education (MINEDUC).

- Individualized coaching sessions. TS staff provide coaching to teachers one–on–one nine times during the school year. After modeling, co–teaching or observing a teacher’s lesson, PoP staff provide individualized feedback that is critical for improving the implementation of new methodologies and materials.

- Community meetings. PoP joined community–wide meetings in January and October of this school year. The goal of these meetings is to increase buy–in from parent leaders in the community, ensure they are aware of the services being offered at their school, and include them in the current challenges and successes.

Photo credit: Amanda Brown

Design & Analysis

The design of a program evaluation is particularly important in enabling valid insights, especially in as complex and dynamic of a research area as student literacy in public schools across Guatemala. I often refer to “just like a good concrete foundation sets up a strong building, a good research design sets up a mathematical inference,” and this absolutely holds true here.

PoP Guatemala is engaged in a longitudinal study to track student literacy score changes over three years: we measure students in both TS and non-TS schools over time, so that we can examine the changes we observe in TS schools as identifiably different from non-TS schools and separable from other coincidental trends occurring over time. This enables us to examine the effectiveness of our work above and beyond the gains, which students make outside of TS programming. Analysis seeks to answer: To what extent does exposure to our programming predict higher student literacy scores, and for which students, and why?

PoP Guatemala uses a modified version of the Early Grade Reading Assessment (MEGRA) for student literacy testing. For this 2019 analysis, we compare the MEGRA scores of 330 students in TS schools with the MEGRA scores of 207 students in non–TS schools. All of these 537 students are measured at Baseline (beginning of the school year) and Endline (end of the school year) in PoP–built schools during the 2019 school year, as a small subset of the students in all PoP-built schools.

Of these 537 students, 48.04% self-identify as a boy while 51.96% of the sample report girl. 264 students (49.16%) are in first grade and 273 (50.84%) are in fourth grade. 458 or 85.61% of students report participating in pre-kindergarten. Additionally, 283 students (52.70%) of students are in bilingual Spanish-Mayan schools and communities as designated by PoP Guatemala, while 254 (47.30%) are in monolingual Spanish schools and communities.

The MEGRA sections are as follows:

- Section 1: Knowledge of Letters

- Section 2a: Phonetics, Onset Sound Recognition

- Section 2b: Phonetics, Segmentation

- Section 3: Simple Words Per Minute

- Section 4: Nonsense Words Per Minute

- Section 5a: Passage Correct Words Identified Per Minute

- Section 5b: Passage Comprehension Questions Correct

- Section 6: Oral Comprehension Questions

- Section 7: Sum of Writing Logistics

Photo credit: Unknown

Results & Learnings

At a high level, results set a positive scene for students in PoP Guatemala schools. TS coaching sessions, workshops, and material delivery components are helping students learn fundamental literacy skills.

This is the first of three years of data collection, and just one star in the full constellation of PoP Learning & Evaluation (L&E) data collection efforts: Teacher Observations, Teacher Interviews, and more are also conducted. However, results this year do not show significant differences in performance growth between TS and non-TS students. While scores support that many students are learning and showing score increases, the gains evidenced in TS schools are not statistically significantly above and beyond the gains in non-TS schools when controlling for other demographic factors (especially this early in the study); the regression shows only mild positive effects for three of the nine sections of the MEGRA (Section 1, Section 2b, and Section 6). Analysis also speaks to other factors that are important to L&E efforts and PoP’s mission.

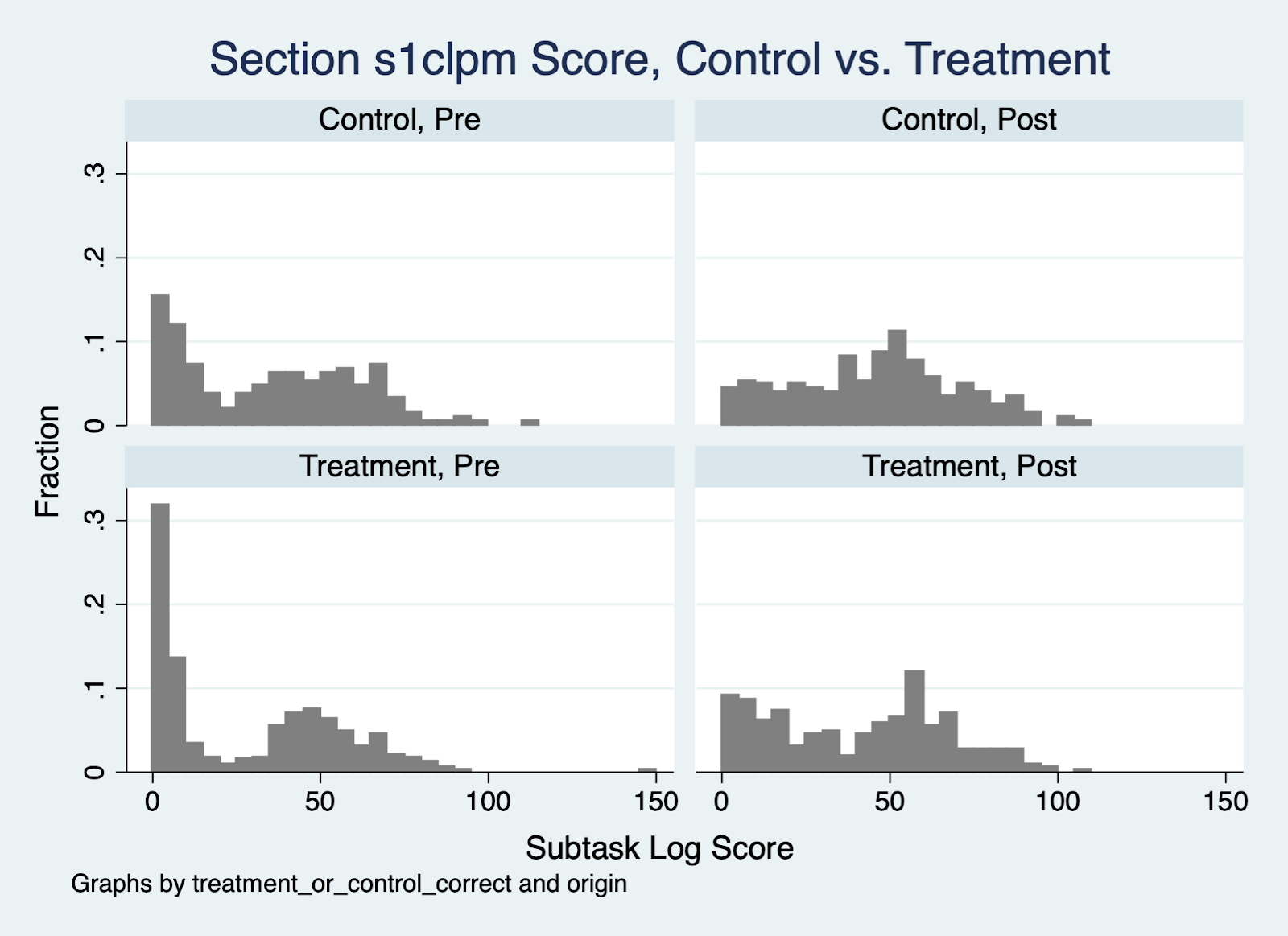

Interestingly, statistical evidence suggests that students in TS schools show a significantly larger decrease in zero scores compared with decreases in non-TS schools, for four of nine MEGRA sections (Section 1, Section 2b, Section 3, and Section 4). This implies that students are not being left behind in these fundamental skills, and that perhaps there is more emphasis by TS teachers than by non-TS teachers to help students who are lacking these fundamental skills. This is visualized in Figure 1, with non-TS (i.e., Control) scores across the top row from Baseline to Endline, and TS (i.e., Treatment) scores on the bottom row.

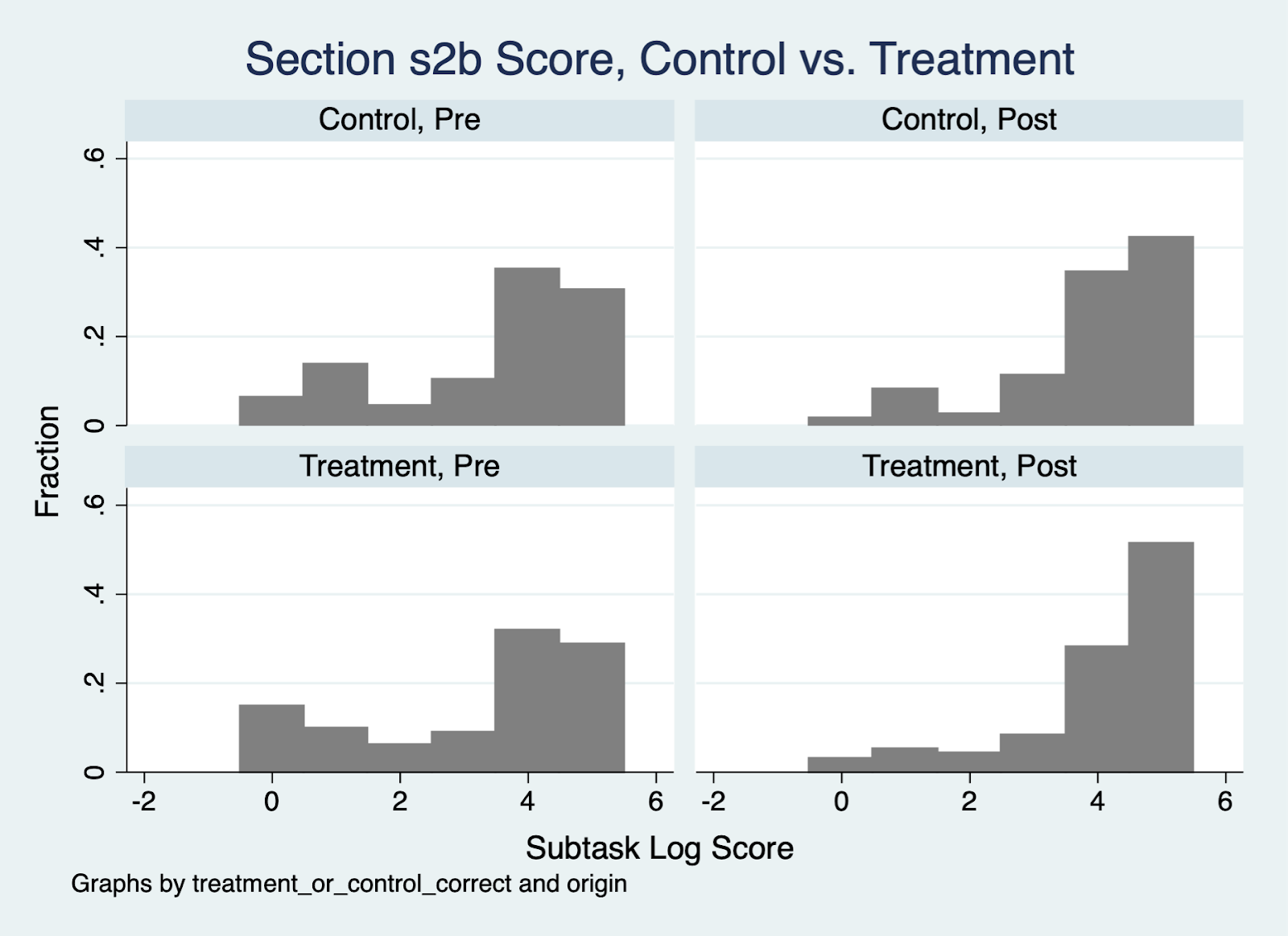

For some MEGRA sections, codifying significant gains in TS schools versus non-TS schools is difficult because scores at Baseline were high for both groups. This is the case for Section 2b (Phonetic Segmentation), and a comforting interpretation made possible by our design: students overall are doing well here, TS schools’ students included (Figure 2).

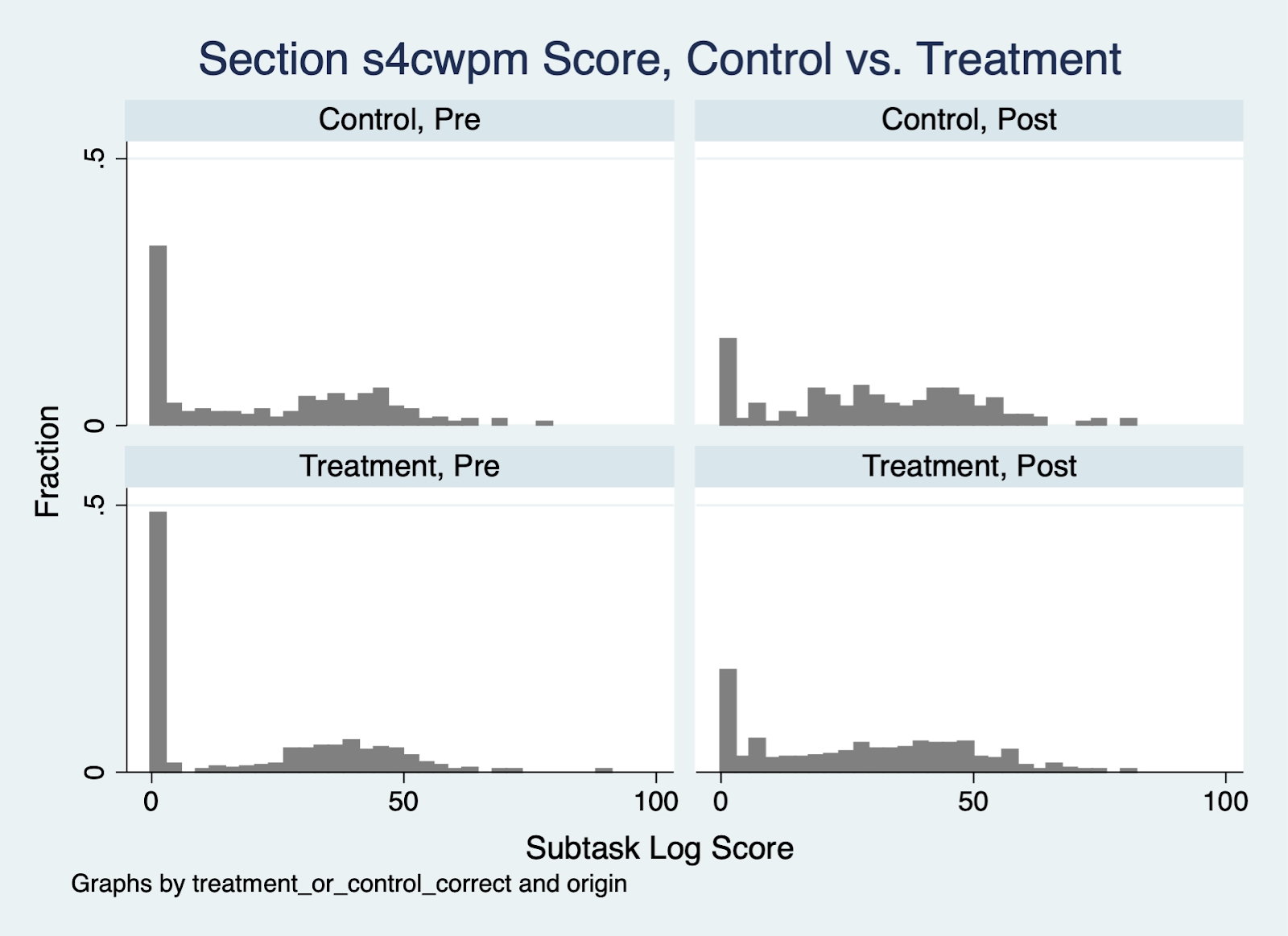

A more typical pattern is illustrated in MEGRA Section 4, ten passage comprehension questions (Figure 3). Here, you can see the TS and non-TS groups start from similar places at Baseline, and the TS group shows a (statistically significant) reduction in the number of students scoring zero from Baseline to Endline. However, the TS scores overall don’t change substantially from each other as they shift in the more positive direction of the distribution, and regression analysis fails to detect significant differences.

Another major finding in analysis is that students in Grade 4 are predicted to achieve a significantly higher score than students in Grade 1 on several sections, as hypothesized. These older students who have had more schooling are performing better; this implies that students over time are learning effectively as they progress through schools; these results are reassuring, and worth pausing on.

Additionally, results also suggest gender equity, in that gender does not have a consistent relationship with student scores. Average scores for boys and girls are about the same in each section at Baseline and at Endline, with girls predicted to score marginally higher in some sections (Section 1, Section 3, Section 5, and Section 7).

Photo credit: Amanda Brown

We ask, then, how can we use these results moving forward? Admittedly, they’re somewhat anticipated: we’re becoming familiar with these patterns, and how to examine them in the context of other evaluation efforts. Substantial student literacy change at scale occurs over a long period of time, and seeing effects beyond a comparison group in just one school year is difficult.

First and foremost, PoP L&E believes our commitments to careful evaluation and collaboration with Programs (i.e., TS and WASH) helps found our results in truth and opportunity. We continue to work hard and return to our core value of learning (as highlighted in my colleague Kara Grieco’s Transparency Talk), and we grow by focusing our discussions on the complexity and reality of public education.

Overall, the results are promising and PoP can look forward to several more years of TS programming and L&E efforts with this cohort study. While it may be difficult to detect learning patterns between our two language groups (given that most students seem to use Spanish at home, rather than many using K’iche’ or Mam), there are many other elements where PoP can gain insight. The longitudinal study, by design, will find greater strength and confidence in these and other results as Programs continues their hard work and as L&E continues to support our common understanding of how effective programming can be, and for whom. Together, these collaborative efforts will allow PoP to shine more light on the complex contexts in which students learn, and iteratively being our work towards greater heights.