What is the relationship between eye contact and the teaching-learning process?

For student learning, is constructing “why” questions the only strategy to generate reasoning?

Asking questions like these help us understand the impact that teacher-student interactions have on the Teacher Support (TS) program at Pencils of Promise (PoP) and, more importantly, provide guidance for how these interactions can be improved to provide a high-quality learning environment. PoP’s Learning & Evaluation (L&E) Team understands the importance of tracking changes in these interactions and works closely with the TS Team to create teacher observation protocols that ask the ‘right’ questions. In Guatemala, we’ve worked to vastly improve our teacher observations and now have an approach that we believe will provide more reliable and valid results for internal program adaptation and external proof-of-concept.

The TS program in Guatemala trains teachers on different reading strategies, which are reinforced during coaching sessions throughout the school year. This part of the program involves a direct interaction between our team and teachers; however, the ultimate goal is to improve the most important interaction in the classroom: teacher-student.

In a classroom, countless interactions happen on a daily basis. These can include making students feel comfortable, managing student behavior, maximizing learning time and providing feedback. With so many different interactions and behaviors taking place, there is a challenge in determining the most appropriate way to evaluate change. Can we structure those different kinds of interactions? Is it possible to measure those interactions? How can we demonstrate that teacher-student interactions have a correlation with student performance? Finding a tool that answers all these previous questions can be intimidating; however, since early 2018, PoP has spent an extensive amount of time adapting and implementing a comprehensive teacher observation form that provides insight into the teachers’ abilities and teacher-student interactions.

Classroom Assessment Scoring System

In the early ’90s, researchers from the University of Virginia, along with the National Center for Early Development and Learning (NCEDL), created the first version of a tool called CLASS (Classroom Assessment Scoring System). This tool helped them observe the quality of interactions, and academic and social development in preschool programs. Teachstone Training, LLC (2015)1 explains that three main research findings were that (1) better cognitive, behavioral and social results are dependent on effective teacher-student interactions; (2) many children are not exposed to effective interactions with teachers that help them grow socially and academically; and (3) real differences in students’ outcomes2 (social competence, better behavior and literacy skills such as early reading and writing) are associated with improvements in teacher-student interactions, no matter how small these are. Following these findings and greater theoretical and empirical research 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, the CLASS system has shown the relevance of the “how” in teaching-learning quality. The CLASS tool goes beyond observing the infrastructure of a classroom, the presence of materials and having a curricula by additionally focusing on how teachers use both books and time, and keep students engaged (Teachstone Training, LLC, 2015).

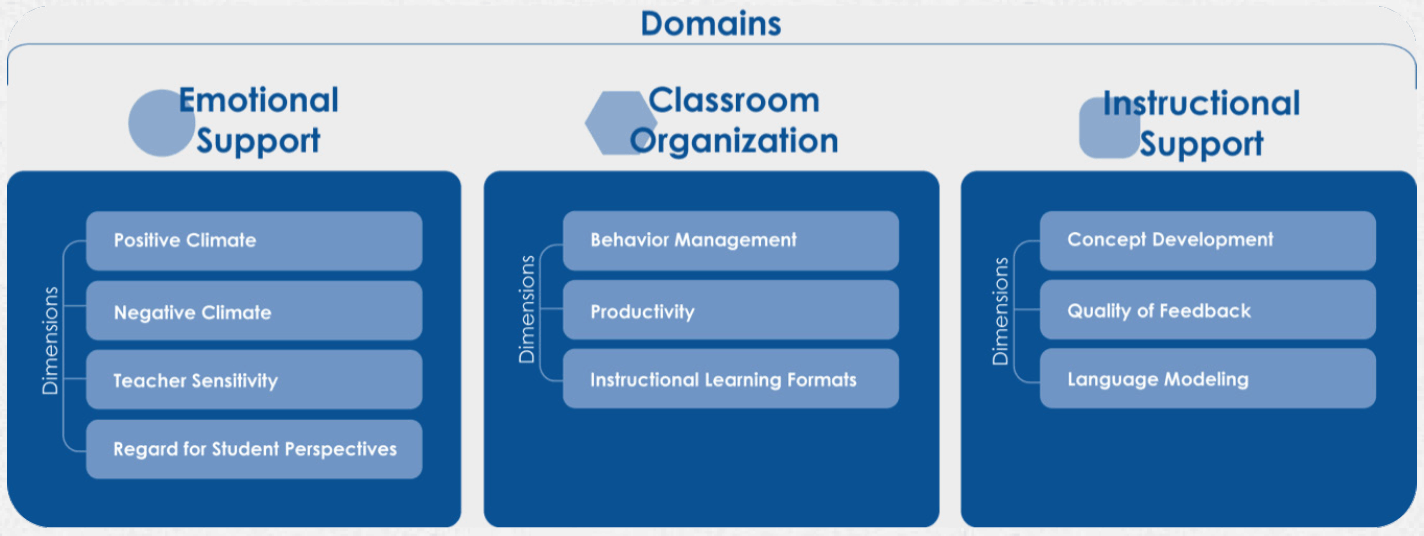

CLASS has different interaction categories that range from broad areas (domains) to specific items observable in a classroom (behavioral markers). First, the tool has three domains which includes ten dimensions. See image below:

Source: Teachstone Training, LLC.

At the most general level, the interactions can be grouped in the following domains:

- Emotional support: focuses on the positive relationships and support between teacher-student and student-student, and the level of autonomy that the teacher provides to students.

- Classroom organization: looks at how the learning time is maximized through time and student behavior management.

- Instructional Support: includes the way teachers promote cognitive and linguistic gains and the delivery of effective feedback.

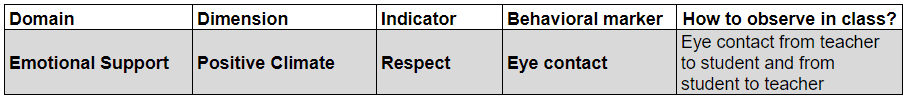

Beyond domains, there are ten dimensions that provide more detail within each domain. Dimensions are explained by 42 indicators, which are identified through several behavioral markers. For example:

See all CLASS structure.

From CLASS to TOG

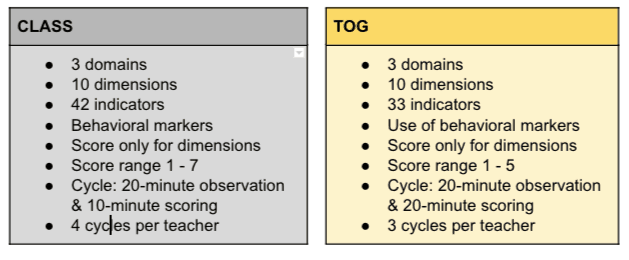

After deciding that CLASS was meeting our needs in both reliability and measurement, the adaptation process to a PoP Guatemala context started. Table 1 shows the similarities and differences between the original characteristics of CLASS and the PoP L&E Guatemala tool, which is called Teacher Observation: General (TOG)-, and the Spanish version: “Teacher-student interaction observations”.

The final tool was developed based on 1) indicators the TS team was indirectly discovering during workshops and coaching sessions and 2) those that could be in the scope of the program. Then, our L&E team held a training with a certified CLASS Observer (previous L&E manager, Aldo D’Agostino) and was ready for field implementation. With our new tool in hand, we started the job of visiting our seven schools receiving the TS program and observing 25 teachers from all grades. During the 2018 school year, we implemented four rounds of observation (April, May, July and September).

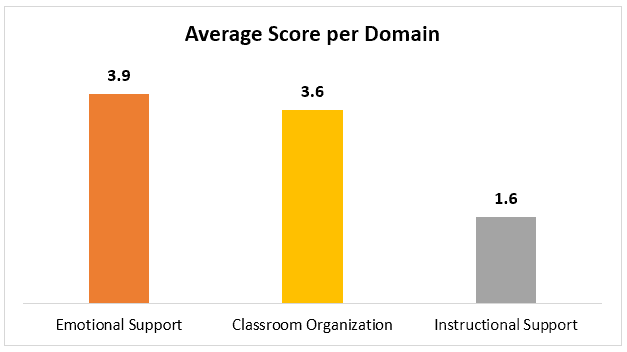

The average score results for 2018 school year are:

For all seven schools, we observe that the domain where teachers need more knowledge and training isInstructional Support. We also concluded that throughout the year, there was some improvement for all three domains. As mentioned before, even small differences in the quality of interactions make real differences in student outcomes.

The journey of realizing the importance of emotional support, and other teacher-student interactions, that teachers can provide continues by sharing observation findings with our TS team. During these discussions, we have learned:

- TOG is another piece of the pie of data that evaluates our TS program (i.e., EGRA)

- TS team relies on TOG as it provides precise information about teaching abilities and short-term feedback

- Knowledge of effective teacher-student interactions is complementary of the interventions we’ve had so far. (i.e., books, reading strategies and coaching sessions)

Having the “what” (materials and curricula) plus the “how” (teacher-student interactions) of classroom quality as part of our TS program ensures a high-quality teaching-learning process and, ultimately, an improvement in literacy. As we move toward a 2019 school year in Guatemala, we are excited to see our evaluation approach put to use with expansion into 18 new schools with TS programming and tracking teachers longitudinally. Our tool and our approach will continue to inform adaptations made within and between years, in addition, to provide evidence to the effectiveness of our influence on improving teacher-student interactions in the classroom.

References:

- Teachstone Training, LLC. (2015). Why CLASS? Exploring the promise of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS). A publication of Teachstone.

- Teachstone. (2017). Effective Teacher-Child Interactions and Child Outcomes: A Summary of Research on the Classroom Assessment. Scoring System (CLASS) Pre-K–3rd Grade. A publication of Teachstone.

- Early, D., Barbarin, O., Bryant, D., Burchinal, M., Chang, F., Clifford, R., et al. (2005).Prekindergarten in eleven states: NCEDL’S Multi-State Study of Prekindergarten and Study of State-Wide Early Education Programs.Retrieved December 1, 2005, from http://www.fpg.unc.edu/NCEDL/pdfs/SWEEP_MS_summary_final.pdf

- Hamre, B.K., & Pianta, R.C. (2005). Can instructional and emotional support in the first grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development, 76(5), 949–967.

- Morrison, F.J., & Connor, C.M. (2002). Understanding schooling effects on early literacy: A working research strategy.Journal of School Psychology, 40(6), 493–500.

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2002). The relation of global first grade classroom environment to structural classroom features, teacher, and student behaviors. Elementary School Journal, 102(5), 367–387.

- Pianta, R.C. (2006). Teacher-child relationships and early literacy. In D. Dickinson & S. Newman (Eds.),Handbook of early literacy research, (Vol. 2, pp. 149–162). New York: The Guildford Press.