Photo credit: Amanda Brown

About the Teacher Support Program: What Do We Do?

Pencils of Promise (PoP) implements our literacy programs with Guatemalan communities who commit to education. Firstly, we build public schools after forming a Promise Committee with communities and conducting a rigorous Needs Assessment. Then, we provide Teacher Support programming to train government teachers (and we provide materials like books and e-readers) to improve students’ reading, writing and comprehension.

Guatemala’s 2018 Teacher Support (TS) program supported 46 teachers in teaching Spanish literacy skills across 7 schools (shout-out to Guate Programs team!). In the 2018 school year, TS programming benefited 853 students. Key components of PoP’s TS program include:

- Group teacher workshops. Workshops are held at the beginning of each of the three academic terms. The goal of these workshops is to integrate new methods into everyday classroom instruction for the curriculum provided by the Guatemalan Ministry of Education (MINEDUC).

- Individualized coaching sessions. TS staff provide teachers one–on–one coaching 13 times during the school year. After modeling, co–teaching or observing a teacher’s lesson for about 45 minutes, PoP staff provide 15–20 minutes of individualized feedback that is critical for improving the implementation of new methodologies and materials.

- Community meetings. PoP joins community–wide meetings twice per year, typically at the beginning of academic calendars. The goal of these meetings is to increase buy–in from parent leaders in the community, ensure they are aware of the services being offered at their school, and include them in the current challenges and successes.

Photo credit: Nick Onken

Design & Analysis

Just like a good concrete foundation sets up a strong building, a good research design sets up a mathematical inference. Since we measure both TS and non-TS schools, we can consider the changes in student scores from TS schools above and beyond the changes in non-TS schools. This enables us to examine the effectiveness of our work above and beyond the gains which students make outside of TS programming.

PoP Guatemala uses the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) for student literacy testing; in this case, we compare the EGRA scores of 295 students in TS schools with the EGRA scores of 341 students in non–TS schools. All of these 636 students are measured at Baseline and Endline in PoP–built schools during the 2018 school year, as a small subset of the 853 students in our 7 TS schools and nearly 40,000 students impacted in PoP–built schools in 2018.

Results & Learnings

Regression results do not show that student test scores in TS schools improve significantly above and beyond the non-TS school gains (when controlling for the influence of several demographic and structural factors). Rather, our analysis doesn’t show students in schools receiving TS improve more than students in our schools not getting the TS program.

However, students in PoP’s TS schools are still improving their literacy skills during the school year. Scores on the EGRA increase in the TS group from Baseline to Endline and the number of students scoring zero on sections of the EGRA drops substantially. While regression results do not show significant effects of TS over non-TS schools, evidence shows that TS schools are still improving substantially.

For some of the nine EGRA sections examined, finding significant gains in TS schools versus non-TS schools is difficult because scores at Baseline were high for both groups. In these cases, the regression results have a hard time demonstrating our program’s efficacy above and beyond Control schools. This is the case for Section 1 (Orientation to Print), and a comforting interpretation made possible by our design: students overall are doing well here, our TS schools’ students included (Figure 1).

Figure 1: EGRA Section 1 (Orientation to Print) Scores, by Pre-Post and Control-Treatment

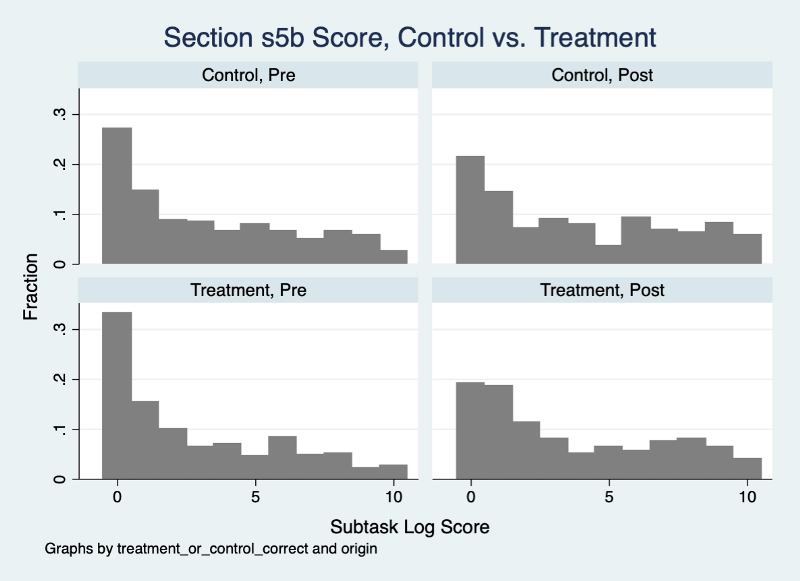

A different and more typical pattern is illustrated in Section 5b, a series of comprehension questions about a passage (Figure 2). Here, you can see the TS and non-TS groups start from similar places at Baseline, and the TS group shows a (statistically significant) reduction in the number of zero scores from Baseline to Endline. However, the TS scores overall don’t change substantially enough, so regression analysis fails to find significant differences.

Figure 2: EGRA Section 5b (Passage Comprehension) Scores, by Pre-Post and Control-Treatment

There are other interesting findings worth noting, too. First is the significance of grade to predict students’ Endline scores. We find that higher grade levels are significantly predictive of higher Endline scores: 1) the higher the grade, the higher the improvement at Endline, suggesting more rapid literacy gains in later grades and 2) higher Baseline scores predict higher Endline scores.

Surprisingly, the regression also shows that language elements like a students’ mother tongue or whether their mother speaks Spanish (versus K’iche, the most common language in the area) does not predict Endline scores. Extensive conversations within the Guatemala team, before this Endline analysis and in preparation of selecting new TS schools for the 2019 school year (i.e., midway through the 2018 school year), led to hypotheses suggesting that mother tongue and mother’s ability to speak Spanish would influence student scores on the EGRA. So, our 2018 results are surprising, yet we still strongly believe there is something to be said for differences of language at home and how well students absorb the Spanish curriculum in Guatemalan schools.

So what does this mean for us? How are we going to study this?

We’ve been seeing results like these for a little while now (e.g. our Ghana Endline); it’s not a big surprise. Literacy changes are incremental, and seeing them above and beyond a comparison group in such a short amount of time (i.e., a single school year) isn’t all that realistic. We ask, then, how are these results best used moving forward, to improve our evaluation plans so that we can provide actionable information to Programs teams?

Firstly, we believe our culture of rigor and our fidelity to the truth gives our challenges and successes a real gravity. We continue to work hard at perfecting our programming, and we move forward by focusing our conversations carefully on the complex reality of education and program evaluation in rural areas of Guatemala. We (maybe especially I) continue to learn from our Guatemala team and how to combine these EGRA results with other metrics (teacher interviews, teacher observations, coaching logs and more).

We have made two foundational changes: 1) as of early February 2019, we’ll be using a modified EGRA (MEGRA), which was developed in close partnership with our Guatemala Teacher Support Specialist, Carlos Mendez, to align more closely to the national education curriculum and 2) we will be tracking student performance over time in a longitudinal study. We’re taking the study design change as an opportunity to understand the impact of TS programming in a new set of 18 PoP-built schools by following students’ scores over three grades (Figure 3). This new design will really help us detect and track changes over the course of multiple years. We’ve set up two language subgroups to investigate differences there as well: 1) bilingual Spanish (BE) for communities where Spanish is predominant language in addition to other Mayan languages and 2) monolingual Spanish (ME) for communities where Spanish is spoken and Mayan languages are not spoken.

Figure 3: Longitudinal Design: Guatemala Teacher Support

Measuring student test scores in two cohorts, year-on-year in a new set of schools, enables us to more clearly identify long term trends and the touchpoints of TS efficacy. We’ll be better positioned to differentiate TS effects from a variety of structural factors (e.g., gender, language group, and living distance from schools) over the course of several years. We believe in the sustainability of our work, which is highlighted by all 204 PoP Guatemala schools, built over the course of seven years, being fully operational to date. Schools with TS programming receive particular attention to make sure we’re dedicating our resources accordingly. We’re setting our students up for success, and now aligning our evaluation efforts with the real-world messiness and complexity we love.